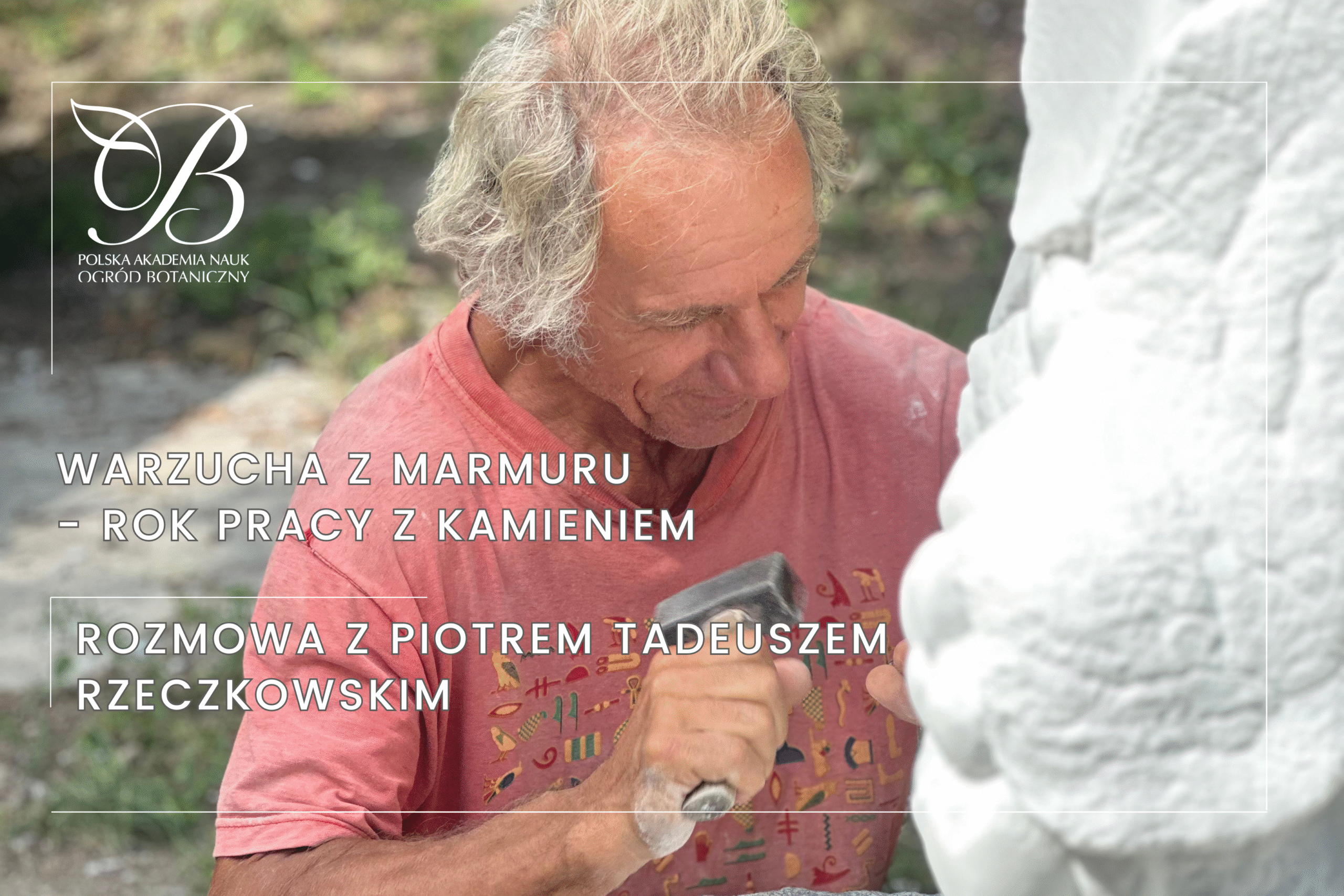

The marble brew. A year of working with stone - a conversation with Piotr Tadeusz Rzeczkowski.

At the Botanical Garden Polska Akademia Nauk in Powsin is creating an unusual sculpture depicting the Polish warbler - an endemic of lowland Poland, miraculously saved from extinction and at the same time a symbol of the Powsin Garden. Its author is Piotr Tadeusz Rzeczkowski, sculptor known for his emotional approach to stone, creator of works in bronze, ceramic, granite and marble, winner of the 1984 Warsaw Uprising Monument competition. He has previously created a granite tree for the Garden, as well as memorial plaques. The sculpture of the warbler will become part of the space of the Botanical Garden of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Powsin. The work is expected to be completed in November 2025, giving exactly one year of work on this organic motif, which is difficult to capture in stone. The artist himself talks about his inspirations, emotions and struggle with stone matter:

How did your artistic path begin? Do you remember the moment when you decided that you wanted to become a sculptor?

I've been very fortunate - really very fortunate - that I've never had a problem With what I would be in life. I just always knew I was going to be a sculptor.

Since childhood?

Since childhood. My mother always said that I was busy with something all the time - plasticine, clay, blocks. My childhood was marked by so-called creative work.

And what was the most important thing for you in art education? What can't be taught, but must be experienced?

The most important thing was to meet an outstanding sculptor - Barbara Zbrożyna. I ended up with her because... I can't draw at all. My mother knew her and thanks to her help I got into Ms. Barbara's studio. Earlier I tried to learn drawing from another painter, but she quickly gave up and just recommended me to Basia - saying: "Go to my friend Barbara Zbrożyna, I will warn her - maybe she will take up, because I can't manage".

So I went to see Ms. Barbara. I had with me a leather bag over my shoulder - in it photographs of my works. I was ambitious, a little butch. I was preparing for college exams myself. I showed her my works - mostly sculptural portraits. She took one look, slightly scowled and said: "As a letter carrier you'll definitely do well". - probably because of the bag. After a moment she added: "Come to the studio tomorrow at nine - maybe we'll work something out."

A little discouraged, but also pleased, of course I came. She had a large, two-story studio in Zoliborz, in Zoliborski Orchards. She gave me specific subjects, which I realized in clay. At that time there was only a month and a half left before the exams for the Academy. I worked intensively and succeeded - I became a student. Later a graduate. And I'll be honest - I learned more in that month and a half with her than in five years at the Academy. Maybe this does not speak well of the academy, but this is the truth.

And the other person who had a huge impact on my life was the then director of the Botanical Garden - Professor Jerzy Puchalski. In 1997, an open-air workshop was held here, organized by the Ministry of Culture and the Union of Sculptors. At that time I was not a member of this union, but a colleague called me: "Come!" I didn't know where it was exactly, so he said: "Get on your bike, go straight, then right - when you pass Warsaw, you'll be in the garden." And indeed - I got there without any problem.

I chose for myself the largest granite that was available. There were only three people left from the plein air at the time - I was the fourth. I started carving a seal. I worked on it for five, maybe six years. The plein-air workshop lasted until the end of October, and I kept coming, shoveling the snow off the sculpture And I was chiseling away at the granite. I made it enough that it had a clearly finished head and an L-like form. But I had to stop - winter and so on, I didn't yet know how to work in winter at that time.

A year later, I returned to the garden. I went to the director: "Is that the seal you were making? Please finish it. No problem." Again, I didn't finish it - but not because I was slacking, it was just that the stone was really huge.

Over the years I made for the garden, among other things, a plaque of Halina Czerny-Safanska, which is located on Fangorovka. I was already known here. The professor said: "Mr. Peter, you don't have to ask anymore, you have an open air here for life - do it". And so it continues to this day - thanks to Mrs. Barbara, who taught me, and Professor Puchalski, who made it possible for me.

Can anyone become a sculptor?

Anyone can become a sculptor, just as anyone can become a priest or a doctor. The only question is whether he will be a good sculptor, a good doctor, a good priest. For everything one must have a vocation. A sculptor must also have a vocation. Anyway, you can see by the works in the public space who was a real sculptor and who just learned it. The foul will always come out.

Well, that's right - because all art involves emotions. It's easy to imagine a painter sitting at a canvas, pouring emotions into a painting. But what does it look like with sculpture? It is, after all, often very hard physical work. Is there room for emotion in it, too?

Definitely yes. Emotions are huge - especially at the beginning. When you have a lump of stone in front of you that weighs several tons, is taller than me, then without real determination, without rage, even aggression - there is no chance. At first this stone is my enemy. He reflects my hostility. But over time we begin to tolerate each other, then to like each other, until finally we become friends. The stone can help me, you just have to listen to it. When it rings hard, you have to stop - he says it hurts, that it's about to fall off. And then from this hostility is born love, and then ecstasy. This is the way - difficult to explain, but true.

A path that often takes several years.

Sometimes they do. Especially since the great masters used to have a whole host of disciples, helpers - one did one piece, another did another... I for my sculptures do not allow anyone. I work without a project. I do everything "on the spur of the moment" - but it's a controlled spur. Every day I come to the studio prepared, I know what I want to do, what fragment to "bite", what to overcome.

Although I must admit that I am not completely alone in this process. I am accompanied by my friend Monika - sometimes she is simply beside me, supporting me with her presence, and sometimes she prompts me as I work. Sometimes her insight from a different perspective opens the door to interesting solutions for me that I wouldn't have noticed on my own. This is extremely valuable to me.

So it's not a stiletto design, but more of a plan shaped as you learn about the stone?

I have an outline - for example, with warzucha I had my stone and I knew I wanted to make a whole plant out of it. But the warzucha is very delicate - the flower petals are the size of the nail of the little finger. And the stone, as soon as I hit it lightly, something fell off. I had to change the concept. And as I changed it - everything moved, "surprised". From then on it was just a matter of time.

I remember those beginnings. I remember Professor Arkadiusz Nowak - the director of the Botanical Garden - coming to you. You consulted on concept changes many times.

Yes, Mr. Professor Arkadiusz Nowak and Dr. Anna Rucińska helped me a lot. I was trying to understand the morphology of warzuca, and I was completely green. Thanks to them I was introduced to this plant. I even have a set of photos, but now I no longer use them - I have this plant in my head.

Can you be called a botanical artist?

A little yes - botanical maybe with a touch of imagination. When I was making a granite tree for the garden, I got a photo from one of the ladies of a dwarf juniper growing on volcanic islands. It was jagged, openworked - perfect. It inspired me. I realized that I didn't want to make a tree "out of a textbook", but something wilder. And I knew - it was just a matter of time. You just have to remember that granite has its own laws. But how to get along with it - it is malleable. Like plasticine, only you have to treat it well.

You work in a variety of materials - which one do you like best?

Stone. Definitely stone - because stone is emotion.

And not bronze, not ceramic?

Ceramics I used to do, I was even an instructor. But it bores me. Bronze? Bronze is not sculpture - you sculpt in clay, wax, plasticine, plaster... and then it's cast in bronze.

And the stone? Stone is a real sculpture. Here you can't add - only subtract. You need to have a clear concept and courage. In stone there is no correcting. Here everything must be thought out and clean.

So you also have to be very attentive and ready for changes - if something falls off, you have to react?

Yes. Although as we are already in an advanced stage of work - we do not want to change anything. But when something falls off, it depends what. Like the nose in the portrait - well, that's a tragedy. It will no longer be that figure. Because in stone we will not touch up - a line, a scar will remain. That's why you need to be careful. Force is needed only at the beginning to break the solid. After that - the more gently you work, the better. Hammer, small strokes - then we bring out the details. To outsiders it is sometimes incomprehensible, but that's how it works.

And in your sculptures, movement, body tension, emotions are often present... Is it possible to capture these elements in working on a plant, too?

Yes. Warzucha Poland, which I am working on now, does not have an inch of straight line in it. Everything is swirling, crooked, delicate - just like in nature. Because in nature a straight line does not exist. Sculpture can't be static. If you make a few verticals - you have static. But when you add bevels, hollows, curves - there is movement, lightness, dynamism. Like this granite tree of mine - all jagged by the wind.

And in the context of warzucha - this particular sculpture - what do you find most challenging? What is the most difficult?

Buds. These buds are the most difficult. I make groups of buds, sometimes single ones, but I have not yet managed to make a bud from which a flower is already coming out. I tried - I didn't like it, so I deleted it. Others said it looks good, but it's me carving - so it's supposed to please me. Therefore, the buds are either closed or open in this sculpture. However, I don't have that moment when the flower "shoots" out of the bud - because in marble it's very difficult. A bud the size of an egg, and a tiny flower is supposed to come out of it? Technically almost impossible.

And why marble specifically?

Because I had such a stone.

So it wasn't about any symbolism, just the availability of the material?

Yes. Although I will say that granite would be better - safer. But for that the work would take much longer, because granite is a completely different hardness, a different pace of work.

And how did you even come to start carving a brew in the garden?

It was the idea of the director, Professor Arkadiusz Nowak. I was asked if I could undertake a sculpture of a warzucha. And at the time I was busy with another sculpture - a realistic female figure. But since it was for the garden - I put that one aside and took on the warzucha.

I was reluctant at first, but quickly got hooked. I began to get an idea - especially since here sculpture is governed by scale. Because if the leaf of a warbler is 5-6 cm, and I made a petal 25 cm long, the leaf would have to be a meter or more! It wouldn't make sense. That's why I manipulate the scale, but keep the morphology of the plant.

This is a completely different subject than the sculptures you usually make.

Yes. But I approach each sculpture as if it were the first one ever. There is no routine. Each one is new and each one must be treated with full concentration.

And how do you manage to transfer the delicacy of this natural form into such a hard material as marble? I think this is a difficult question, but an important one.

Not so hard. Marble is hard at first - just like granite. But the more gently one "knocks" at it, the friendlier it becomes. If you treat it with a hammer from behind the head - chunks fall off. But once I break through the first layer, reach deeper - the stone begins to cooperate. It is a very friendly material, if you approach it properly.

And what does such a creative moment look like in your work? Is it more like meditation, stillness, or a sudden explosion of an idea?

At an advanced stage I already know what I want to do - that here will be a bud, here a leaf, here a flower. This is not meditation - I just sit down and do. Sometimes there are emotions, sometimes there is stability. It depends.

And how do you know when a sculpture is finished? When do you know, "It's done"?

It's simple. If the hand does not fly - it means that it is done. Any further touch with the chisel would already be a cut on what has been created. The sculpture itself says that it is already the finish line. If the next day I see that something needs to be corrected - it means that it was not finished. But if the hand stops naturally - I know it's over.

That is, the stone says...

Yes, but you have to be able to listen to him. One has to be in dialogue. Stone is a living matter - just like wood. Even after three hundred years, wood can react to weather, temperature. Stone is also alive.

And how do you see the Polish brew in the garden space?

The breweri was to be the centerpiece of a pantheon of extinct plant species in Poland - such as pasqueflower, Baltic gentian, flax canarygrass, corn earwort, four-leaved marsupial, slender forget-me-not, Silesian penstemon, stemless primrose, single-leaved susceptor... In this stone circle - like Stonehenge - in the center was to be a fountain with a miraculously saved from extinction breweri.

I see it... This stone is drilled, because the brew likes water. It's supposed to be a fountain - but not one that gushes upwards, but one where the water gently flows down. From the top, down, all over the sculpture. Everything is designed so that there is no place where the water can stop and form a basin. Everything has been thought out - I check it, pour water over the stone and watch it flow.

So you can say that too - such a strategic approach. Because in addition to the artistry and reflection of the living plant, you still have to take into account that this water should not be left anywhere - I understand that it could then harm?

Well, yes. Well... unfortunately this water. I so came up with the idea that it should also be a fountain, because it will be a cool effect. But I'd like this water to be let loose only when a group is there, or when someone is watching - not like 24 hours of dripping water. It doesn't make sense. Because the marble - that marble from Greece - he doesn't like that climate. I don't like it either - it's too wet.

And did you know warzucha before? Or only since this project?

I didn't know. I had no idea at all that such a plant existed. I got photos, prints, I also went to see it live. I had to learn it. But this is also interesting - this kind of work, where I first get to know the subject, learn it, and then translate it into stone.

So it was a kind of scientific and artistic process?

Yes, definitely. And that's what drew me in. Anyway, I like this kind of thing - if something interests me, I can sit and knock for weeks.

If you were to invite visitors to the garden, to look at a sculpture of a warbler - what would you tell them?

Oh no... No, I have never been a cabot. And so I would go on to say: "Well, yes. It worked out for me."

Do you have a favorite spot in the Botanical Garden?

This studio. Once that studio, and now - this studio.

So you have been moved with your studio to another area of the garden? So you could say that visitors to the Botanical Garden, if they go far enough and deep into the garden, then they can meet you at work?

In the previous studio I was, so to speak, among the people, visiting the garden. Even when I did this seal, twenty-seven years ago or more... This fence - because it was a tennis court - was not yet so overgrown with vegetation. There was a clearance. And once this seal was very visible, people from behind the fence were taking pictures, filming me. And even some country that came every year... I did it for probably five or six years - they came regularly.

And then this seal went to the Warsaw zoo, where it stood for almost twenty years. And these states came and ask: "And where is this sculpture?". And I say, "Well, it's in the zoo in Warsaw." "Oh, then we won't come to the zoo anymore, because we came for you."

And is there anything else you would like to add to this whole creative process?

No... because I have already said everything. However, in terms of the creative process - what can I say? Well, I'm just eternally grateful to the management for tolerating me... on its premises.

He tolerates in his territory and even more than tolerates, because he also likes and recognizes a lot.

Mr. Peter, thank you so much for this candid, passionate and extremely inspiring conversation. It is an honor to hear so much about your path, creativity and love for sculpture And to the Garden. Thank you.

A meeting with Piotr Tadeusz Rzeczkowski is not just a conversation about sculpture - it is a meeting with a man who treats his work as a life mission, and stone as a partner In dialogue. He passionately talks about the emotions surrounding the work, the path he has walked and about the people who had a key influence on his development. His sincerity, humility and extraordinary sensitivity show that behind each sculpture is not only the workshop, but also the heart.

The artist has been working for years among the greenery of the Botanical Garden of the Polish Academy of Sciences, where visitors - going far enough - can see him at work. His presence here is a non-accidental continuation of a path that began with plasticine as a child, through many years of study and hundreds of hours with a chisel in hand, to contemporary realizations that fit into the space of nature. This meeting makes you realize that sculpture is more than a form - it is a relationship, a process and a story. And sometimes the seal, which over the years has attracted loyal visitors to the garden, just to see her - and him - one more time.

One of the artist's latest works will be a sculpture of the Polish warbler, a plant that has become a symbol of the Botanical Garden of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Saved at the last moment from extinction by the staff of the Botanical Garden in Krakow, then multiplied and restored in the springs of the Krakow-Czestochowa Upland, it is a symbol of Polish flora conservation - it is the only endemic among the flowering plants of our country occurring in the lowlands. Immortalized in stone with the same sensitivity with which the Powsin garden protects its unique species, this sculpture is a reminder of how closely art and nature can coexist. A sensitive artist who can talk to stone can certainly also admire the beauty of plants, and through his work appeal for their protection and preservation.